The Renaissance

and the Modern World

The14th

century Italian Renaissance was a transition between the Middle Ages and the

modern world. Developing out of the city-state commercial societies of Northern

Italy, it had evolved by the 15th century into the exploration of

both the globe and of humanness, the latter in the vernacular of the Christian

religion of the Middle Ages and in the spirit of the classics of Greece and

Rome. In that century began the exploration of the human condition, with all

its complexities. We hope this spirit will continue in the world of the

present. 1

The

Italian Renaissance

The

Louvre in Paris is the largest art museum in the world. In 2018 it had more

than 10 million visitors, more than three-quarters from foreign countries,

testifying to its universal appeal. In 2019, it opened a blockbuster exhibit

chronicling the life and work of Leonardo da Vinci (Léonard de Vinci), mainly

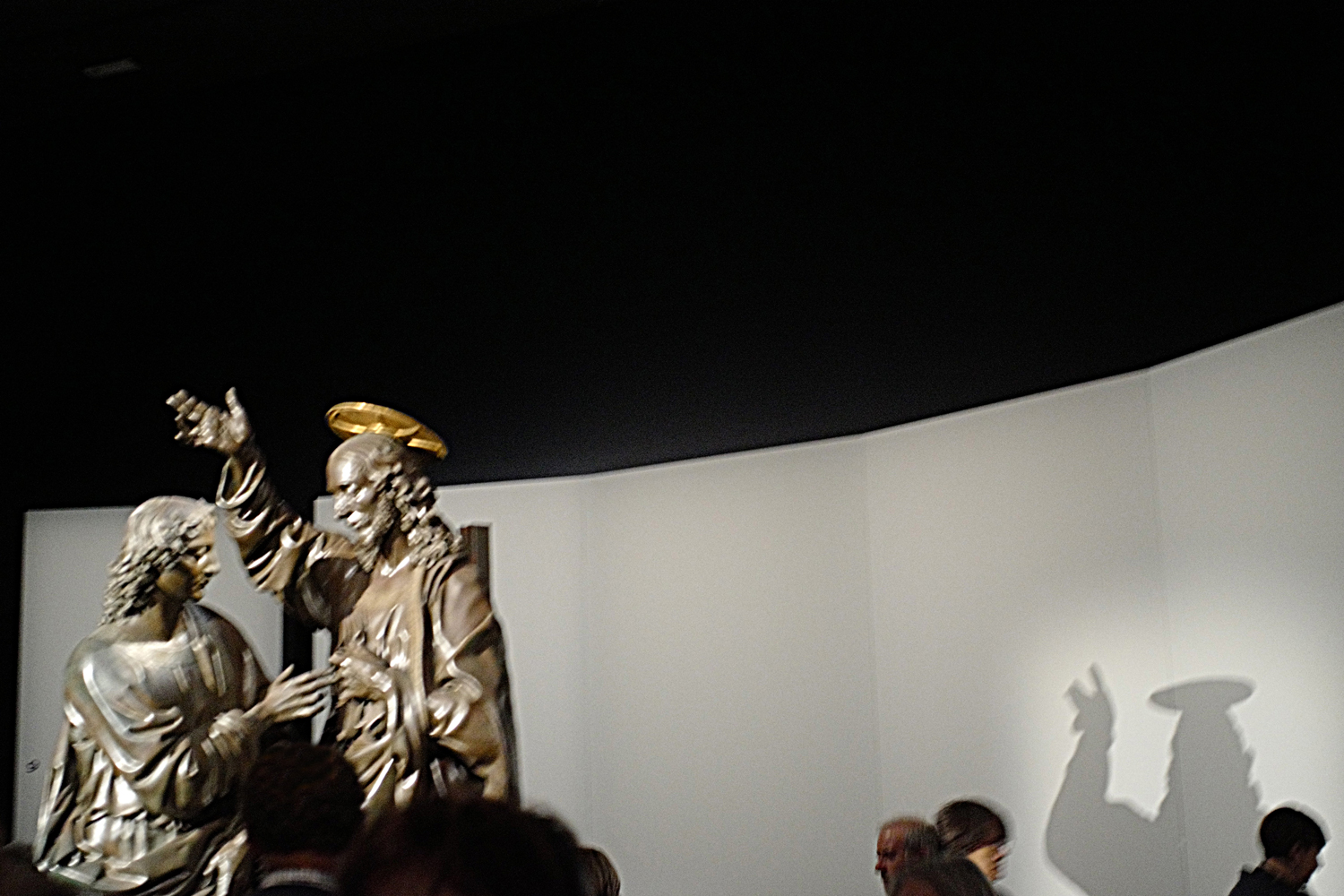

sponsored by the Bank of America. The exhibit opens with statues from a church

in Florence, Italy by Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-1488), a sculptor who taught

Leonardo. The composition of both is called “The Christ and St. Thomas.” In

this installation, the figure of the risen Christ is pivotal and is an

introduction to the rest of the exhibit:

Christ

is now perfection itself, a perfection now inaccessible to humanity, who like

those caught in Plato’s cave, can only see the shadow world of appearances

derived from the perfect world of ideas built by the intellect (classes, in

modern computer languages). But on the other side is his disciple, St. Thomas,

doubting and fearful, and as the exhibition catalogue notes, “…(his) garments

are an expression of the invisible states of the soul and of the spirit. The

garments of Thomas speak of the torments of disbelief, the desire to see and to

touch (the wounds from the crucifixion), the fear of touching and the regret of

having seen the blessedness, forever imperfectly.”

Leonardo’s

goal was a science, making painting a life-like depiction of the real world. In

order to do so, he became an acute and systematic observer of the natural world

and an engineer, creating only around fifteen paintings, some continually

revised in a process called pentimento. The almost priceless

masterpieces that we see today did not just happen by acts of inspiration or of

will. They were the result of years intensely studying anatomy, engineering and

perception. In the next room, the Louvre displays some of Leonardo’s more than

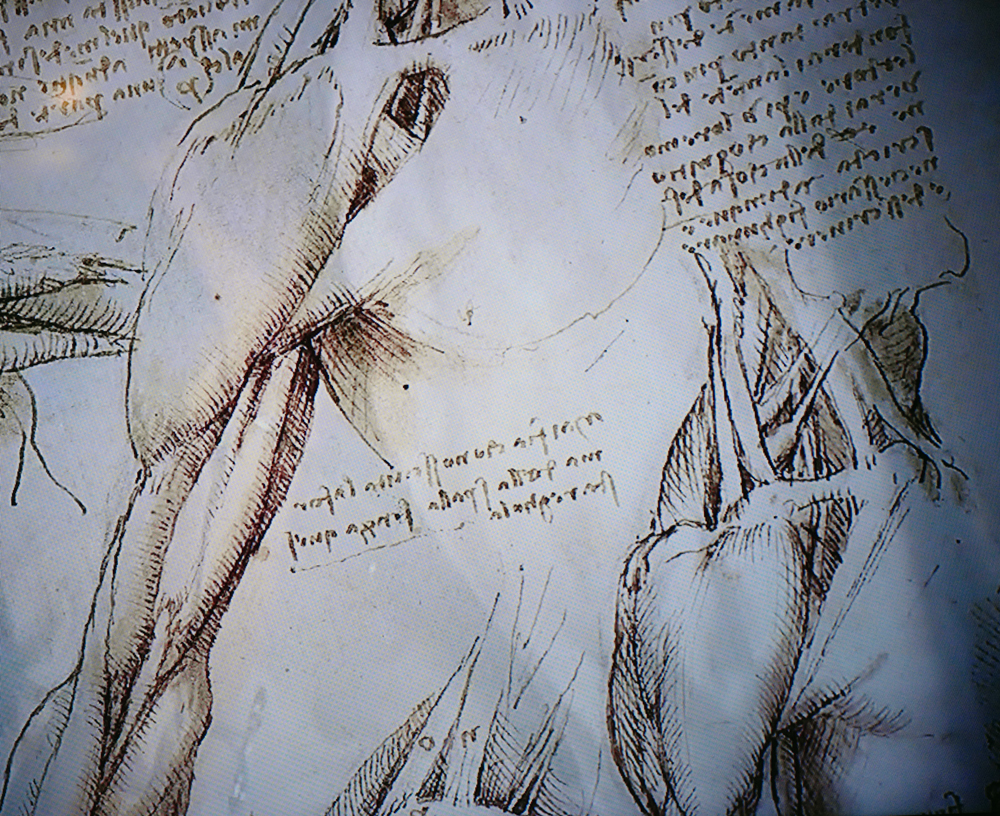

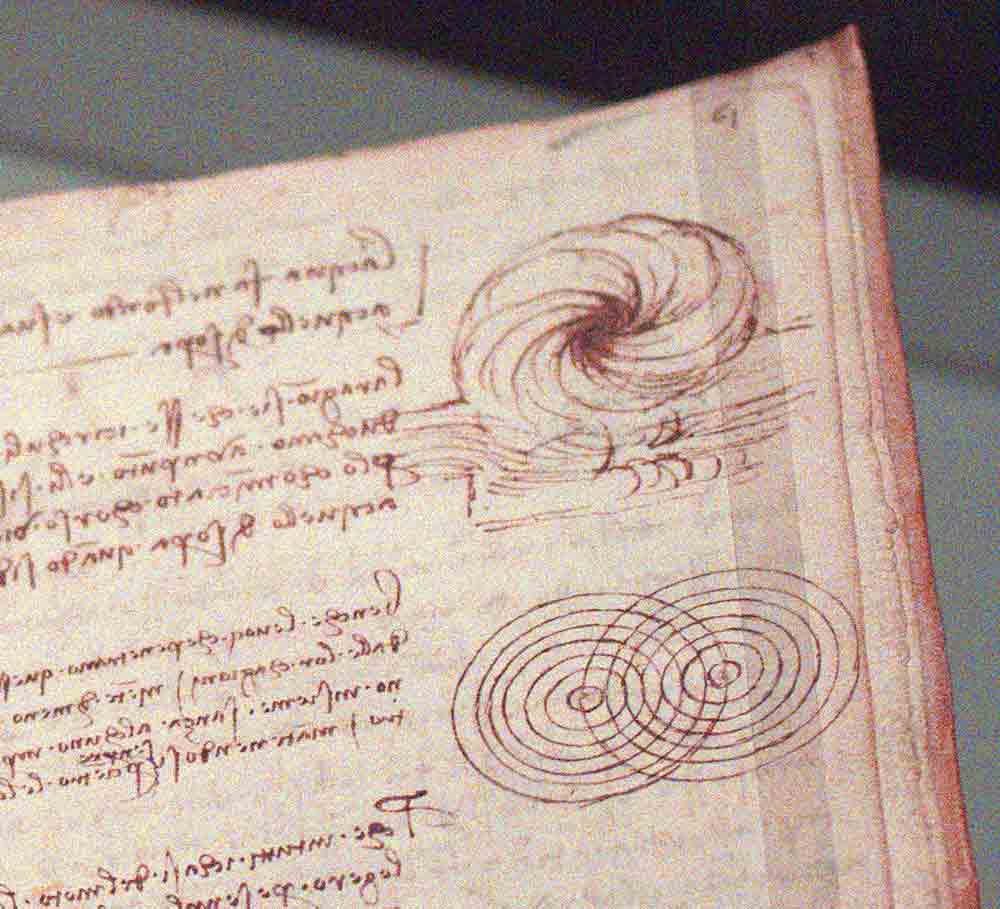

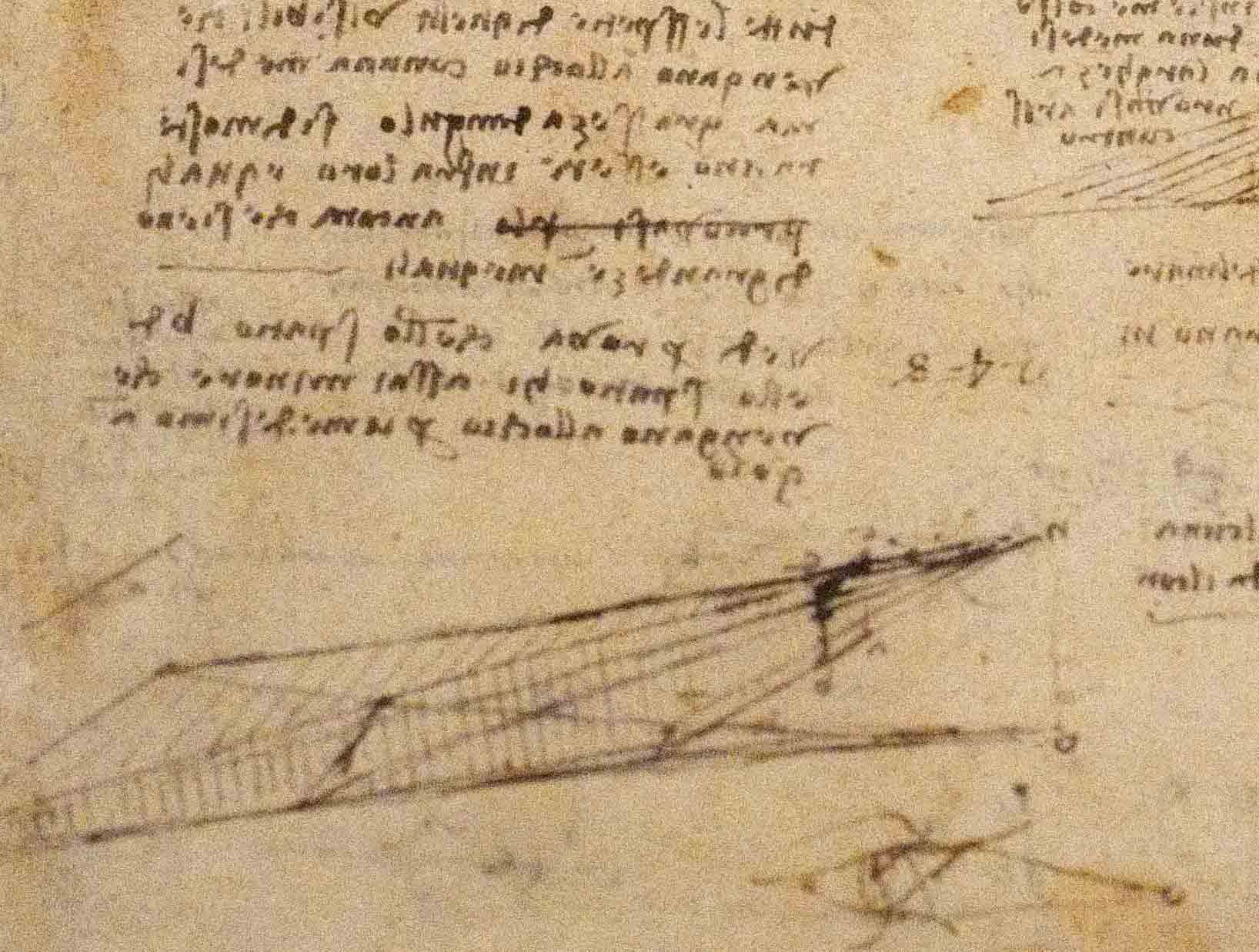

fifty notebooks. We note three excerpts from these 2:

an arm

water turbulence and wave interference

reflections

of light on a cloud

Each of these studies is of a natural phenomenon that Leonardo

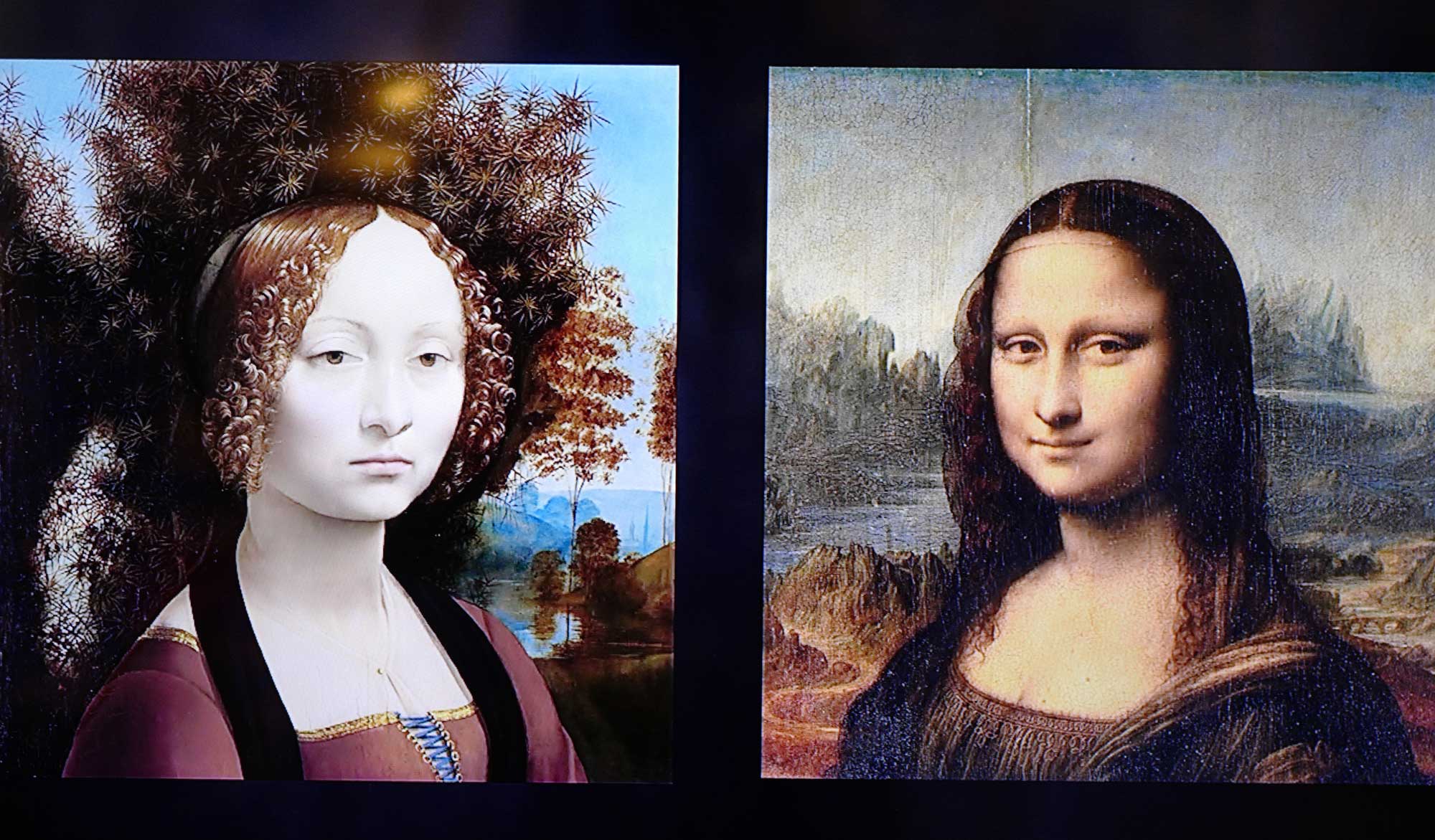

(1452-1519) observed. Now, if you compare his painting of Ginerva de’Benci

painted in 1475 with the Mona Lisa and her enigmatic half-smile begun in 1503

and continually revised until about 1517, you can see what his acute

observations of nature and of perception added.

There’s more. If you look directly at the Mona Lisa you will see

her enigmatic smile with the high-resolution portion of your eye. Then look

slightly away using its lower-resolution peripheral vision. You will then lose

all the subtlety and see only a broad smile. Click here for an enlargement.

While seeking to perfect an art that was true to life,

Leonardo lived in the Renaissance world of political turmoil. In 1494, Charles

VIII of France invaded Italy to favor the Duke of Milan against the King of

Naples. This invasion marked a series of French and Spanish interventions in

Italy that lasted for sixty-five years, ending the Renaissance and its tolerant

world open to innovation. The Louvre exhibit alludes to this, noting “His

contemporaries saw Leonardo as the forerunner of the modern style because he

was the first (and probably only) artist capable endowing his work with an

awe-inspiring realism. Such creative power was as overwhelming as the world

inhabited by Leonardo – a world of impermanence, universal destruction,

tempests and darkness.”

The Modern World

Like the Italian Renaissance, the present liberal world order

focuses on what is valuable in humanity and in the world. Who now remembers

Charles VIII? But this order is now being called into question. Its largest

failure has been to erode the well-being of its middle classes, upon whom

democracy depends. We note the following reactions:

Donald Trump, President: “I alone can fix it.” 3

Can he?

Under the theory that there is a tradeoff between economic equity

and efficiency, in 2018 the Trump administration cut corporate and income

taxes. But economic growth increased beyond the promised 3% for only a couple

of quarters, before relapsing to around 2.1% at the beginning of 2020. CBO

projections now predict trillion dollar budget deficits beginning in 2020 for

as far as the eye can see.

By valuing personal loyalty above competence, Trump has

hollowed out the State Department and is now on the way to hollowing out the

Department of Justice. Next will be the U.S. military. These organizations will

eventually fail to do their jobs well.

The Greeks had a saying, “Character is destiny.” If the

electorate is indifferent to the bad character (not just a few rough edges) of

an angry, divisive and tweeting President, it will be unable to recognize and

to remedy the causes of the nation’s decline. Democracy can end with

indifference.

Thomas Piketty, French economist: “Above all, (social)

questions are complex in a manner that does not at all justify their

abandonment to a small case of experts. On the contrary, their unique

complexity enables us to hope for progress by a vast collective deliberation,

founded on the reasons, pathways and the experiences of all things by all.” 4

Jedidiah Purdy, Columbia University Law Professor: “A

democratic people should be able to hope that, over time, it is improving – not

just getting richer, but understand more of how it intends to live and coming

closer to that ideal. For this to make sense, it’s members must be able to step

outside the present and call on a better version of the country. They will call

on familiar stands of dissent, of course-religious prophecy, constitutional

ideals, practices of civil disobedience-to show that they are addressing the

present from a possible imagined future. A democratic culture gives its members

the means to speak to one another in this way. It troubles our simpler premises

-neutrality and non judgement-but strengthens essential democratic powers: to

criticize, exhort, and change ourselves” 5

How do we solve the complex problems of global warming,

epidemics and an economy that fails to address the needs of a majority of its

people? The first quote is obviously authoritarian, “I alone can fix it.” The

second and third quotes properly rely upon the people in democratic society to

demand change. The Leonardo exhibit, however, addresses the crucial importance

of expertise, necessary to solve difficult real-world problems. In his second

term, both President Obama and House Speaker, Paul Ryan, could agree (at least

in theory) that problems needed to be solved.

But what are the solutions? The above problems cannot be

solved without expertise, to know, for instance, that planting a trillion trees

will not solve the problem of global warming, to design electric grids with

adequate storage capacity. For global warming, the crucial variable is the

effective control of atmospheric carbon dioxide. For epidemics, the crucial

variable is the early identification of those who are sick. For the very

complicated issues of economic reform, decisionmakers deserve better than

canned ideologies. Our next article will discuss practical economic theory.

Footnotes

1.

This exhibition is notable because it exemplifies how

historians think of history as a resource, rather than a linear progression

that results in us. In 1931, the president of the American Historical

Association, Carl Becker, noted to his colleagues that history’s “proper

function is not to repeat the past, but to make use of it, to correct, and

rationalize for common use.” * We were very surprised to find that this exhibit

was organized with this goal, to address a very complex world where the center

is in danger of not holding.

Historical analysis is essentially fact based

story-telling, the way that humans communicate complex ideas and events. Our

analysis of the Renaissance considers: context (in which events unfolded), contingency (about the potential

for change) and agency (what people say and do). By doing so, it endeavors to

explain the past and to make the needs of the future somewhat clearer.

Just so you

know where we’re coming from. During our Jesuit high school educatio, we

studied

years of Latin, an effort that got us into Stanford where we encountered

Western

Civ and what

our instructor said…

* “France

in the World”; edited by Boucheron and Gerson; Other Press; New York,

N.Y.; 2019; p. xv.

2.

The first and fourth illustrations are from PBS NOVA;

“Decoding da Vinci”; Season 46; Episode 21. The second and third are from the

exhibit.

3.

Donald Trump; Republican National Convention; 7/21/16.

4. Thomas

Piketty; “Capital et Idéologie”; Editions du Seuil; Paris, France; 2019; last

paragraph Kindle version. The May/June, 2020 issue of Foreign Affairs writes:

“The advantage of liberal capitalism resides in its political system of

democracy. Democracy is desirable in itself, of course (our note: this issue is

often missing in contemporary political discussion), but it also has an

instrumental advantage. By requiring constant consultation of the population,

democracy provides a powerful corrective to economic and social trends that may

be detrimental to the common good.”

The May/June, 2020 issue

of Foreign Affairs writes: “The advantage of liberal capitalism resides

in its political system of democracy. Democracy is desirable in itself, of

course (our note: this issue is often missing in contemporary political

discussion), but it also has an instrumental advantage. By requiring constant

consultation of the population, democracy provides a powerful corrective to

economic and social trends that may be detrimental to the common good.”

5.

Jedidiah Purdy; “After

Nature”; Harvard University Press; Cambridge, Massachusetts; 2015; p.286.